WEEK 11: SUPERVISOR SESSION

Preparation

I took more pictures and read … not sure what to do with my readings though.

R E A D I N G S

Solnit, R., 2014. Wanderlust: A History Of Walking. Granta Books.

»While walking, the body and the mind can work together, so that thinking becomes almost a physical rhythmic act – so much for the Cartesian mind/body divide. Spirituality and sexuality both enter in; the great walkers often move through both urban and rural places in the same way; and even past and present are brought together when you walk as the ancients did or relive some event in history or your own life by retracing its route. And each walk moves through space like a thread trough fabric; sewing it together into a continuous experience – so unlike the way air travel chops up time and space and even cars and trains do.«

»There is in fact a sort of harmony discoverable between the capabilities of the landscape within a circle of them miles' radius, or the limits of an afternoon walk, and the threescore years and ten of human life. It will never become quite familiar to you.«

»[…] thinking is generally thought of as doing nothing in a production-oriented culture, and doing nothing is hard to do. It's best done by disguising it as doing something, and the something closest to doing nothing is walking. Walking itself is the intentional act closest to the unwilled rhythms of the body, to breathing and the beating of the heart. It strikes a delicate balance between working and idling, being and doing. It is a bodily labor that produces nothing but thoughts, experiences, arrivals.«

»Walking, ideally, is a state in which the mind, the body, and the world are aligned, as though they were three characters finally in conversation together, three notes suddenly making in conversation together, three notes suddenly making a chord. Walking allows us to be in our bodies and in the world without being made busy by them. It leaves us free to think without being wholly lost in our thoughts.«

»Moving on foot seems to make it easier to move in time; the mind wanders from plans to recollections to observations.«

»The rhythm of walking generates a kind of rhythm of thinking, and the passage through a landscape echoes or stimulates the passage through a series of thoughts. This creates an odd consonance between internal and external passage, one that suggest that the mind is also a landscape of sorts that walking is one way to travers it. A new thought often seems like a feature of the landscape that was there all along, as though thinking were traveling rather than making.«

»Walking can also be imagined as a visual activity, every walk a tour leisurely enough both to see and to think over the sights, to assimilate the new into the known.«

»Although I came to think about walking, I couldn't stop thinking about everything else, about the letters I should have been writing, about the conversations I'd been having.«

»Many people nowadays live in a series of interiors – home, car, gym, office, shops – disconnected from each other. On foot everything stays connected, for while walking one occupies the spaces between those interiors in the same way one occupies those interiors. One lives in the whole world rather than in interiors built up against it.«

»The multiplication of technologies in the name of efficiency is actually eradicating free time by making it possible to maximize the time and place for production and minimize the unstructured travel time in between. New timesaving technologies make most workers more productive, not more free, in a world that seems to be accelerating around them. Too, the rhetoric of efficiency around these technologies suggests that what cannot be quantified cannot be valued – that that vast array of pleasures which fall into the category of doing nothing in particular, of woolgathering, cloud-gazing, wandering, window-shopping, are nothing but voids to be filled by something more definite, more productive, or faster paced … As a member of the self-employed whose time saved by technology can be lavished on daydreams and meanders, I know these things have their uses, and use them – a truck, a computer, a modem – myself, but I fear their false urgency, their call to speed, their insistence that travel is less important than arrival. I like walking because it is slow, and I suspect that the mind, like the feet, works at about three miles an hour. If this is so, then modern life is moving faster than the speed of thought, or thoughtfulness.«

Popova, M., 2015. Wanderlust: Rebecca Solnit On How Walking Vitalizes The Meanderings Of The Mind. [online] Brain Pickings. Available at:

»[…] Swiss modernist writer Robert Walser captured this spirit in his short story “The Walk”, which includes this exquisite line: With the utmost love and attention the man who walks must study and observe every smallest living thing, be it a child, a dog, a fly, a butterfly, a sparrow, a worm, a flower, a man, a house, a tree, a hedge, a snail, a mouse, a cloud, a hill, a leaf, or no more than a poor discarded scrap of paper which, perhaps, a dear good child at school has written his first clumsy letters.«

Wegner, J. and Amend, C., 2020. Ólafur Elíasson, Kann Kunst Die Welt Retten?. [podcast] Alles gesagt?. Available at:

»Ich habe eine sehr schöne Leuchte mit monofrequentem Licht gemacht. Diese Lampe habe ich dann in das Fenster gestellt, so dass sie die Straße vor dem Laden angestrahlt hat. Also typisch dem privaten Sektor, den Versuch die Fußgängerzone zu kolonialisieren und einzunehmen. Das Projekt heißt Eye See You, das war so wie ein Auge gestaltet, d.h. man guckt rein und sieht sich selber, man guckt raus und sieht die Leute.

Die Schaufensterscheibe hat auch Richard Sennett beschrieben: Die Glasscheibe als social boarder. Statt ins Fenster rein zu kucken, sieht man insbesondere das Glas durch das man durch guckt. Das ist eine Grenze, keine Öffnung, keine Tür.

Mit dem Louis Vuitton team habe ich daran gearbeitet, wie kann man die Beziehung zwischen drinnen und draußen hinterfragen.«

»I made a very nice lamp with mono frequency light. I then put this lamp in the window so that it lit up the street in front of the shop. So, typical for the private sector, trying to colonize and take over the pedestrian zone. The project is called Eye See You, it was designed like an eye, i.e. you look in and see yourself, you look out and see the people.

Richard Sennett also described the window: the glass pane as a social boarder. Instead of looking through the window, you see the glass you are looking through. That's a limit, not an opening, not a door.

I worked with the Louis Vuitton team on how to question the relationship between inside and outside.«

Marling, K., 1991. The View Through the Plate-Glass Window. New York Times, [online] Available at:

»[…] the skyscraper affords total isolation: the view through the plate glass window reduces street life to the status of a framed picture, unthreatening yet bogus – “sight … routinely insulated from sound, and touch and other human beings”.«

Liu, C., 2011. The Wall, the Window and the Alcove: Visualizing Privacy. Surveillance & Society, 9(1/2), pp.203–214.

»In The Craftsman, Richard Sennett has a surprisingly positive account of border areas, or the region along boundaries. Sennett describes porous, life-giving boundaries as places where exchanges between inside and outside are intensified rather than suppressed: Sennett calls these boundary spaces “living edges”. Security-oriented walls aspire to making boundaries into strictly policed spaces where very little can happen: these boundaries are what Sennett calls “dead edges”. If security and privacy are essential motivators for wall building, “[t]he plate glass window walls used in modern architecture are another version of the boundary: though these windows permit sight within, they exclude smell and sound and prohibit touch” (Sennet 2011: 226–7). In his earlier work, Sennett cites Siegfried Giedion’s description of the glass wall as promoting an ideal of permeability (Sennett 1977: 13). The transparency of glass promotes an illusion of permeability that actually promotes hermeticism and separation.«

»In the 19th century city, anonymity guaranteed a certain degree of privacy – in public. New urban spaces allowed for strangers to occupy the same continuous physical space while being entirely to self-absorbed in private exchanges. The visual and spatial interpenetration of public and private lives and selves became one of the hallmark experiences of the modern city. Confusion and fusion of public and private spaces emerge in modern life as one of the critical dimensions of a democratic and popular visibility. On the street, in department stores, arcades, brothels and boudoirs, images of desire and seduction existed at the crossroads of private tastes and public spaces, forming the dream-like world of commodity fetishism over which the detached gaze of the connoisseur, the real estate speculator and the flaneur could linger. For Richard Sennett, the city is a “human settlement in which strangers are likely to meet” (Sennett, 1977, p. 39). In order to feel at home in a crowd of strangers, the modern urbanite had to learn the art of discretion, or when to avert her gaze when she is thrown into spaces of temporary intimacy.«

»The patient was engaged in the modern project of struggling to find a language of authentic self-representation in order to be capable of true acts of self-assertion. Typical neurotic complaints focused on the inability to recognize oneself in one’s life or one’s condition. Patients felt themselves to be controlled by inscrutable forces, whether demiurgic or unconscious, and it was to be assumed that their private suffering made them incapable or unwilling to participate fully in normative activities in the public sphere.«

Athens, Lonnie. The Self as a Soliloquy. The Sociological Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 3, 1994, pp. 521–532. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4121225. [Accessed 6 October 2020].

»George Herbert Mead recognized more than anyone else that the self emerges and is sustained through soliloquizing. The virtue of visualizing the self as a soliloquy is that anyone at anytime and at any place can easily confirm that it exists by merely engaging in a moment or two of self observation. People need only ask themselves: “do I talk to myself?” If the answer is “yes”, then they have verified their selves’ existence. Thus, envisioning the self in this way avoids making it a mysterious, metaphysical entity defying verification.«

»Mead envisions the self as a soliloquy in two, not wholly interchangeable ways. The most poetic way in which he (1912; 1913; 1934) views it is as a conversation between an “I” and a “me” (Mead 1934, p. 175). The “I” represents the impulse or inner urge to act, as well as the later expression of the impulse in overt action. “The ‘I’ both calls out the ‘me’ and responds to it” (p. 178). Conversely, the “me” represents the perspective of the other from which the “I” is viewed. “The ‘me’ is the organized set of attitudes of others which one himself assumes” (p. 175). It is what enables us to exercise conscious control over our actions so that they will not deviate from other people’s expectations.«

»This lesson is that the self should be viewed as a fluid process that contains a critical, although mutable constant (Zurcher 1977). In my opinion, the self’s fluidity must be seen as arising from our ever-changing soliloquies; while its constancy must be seen as coming from the stability of the “other” with whom we soliloquize. Finally, the part that the “other” plays in our soliloquies must be envisioned in a way that can account for both conformity and individuality in our society, something which Mead could never consistently explain.«

»PRINCIPLE SEVEN

Soliloquizing operates on both a surface and deep level.«

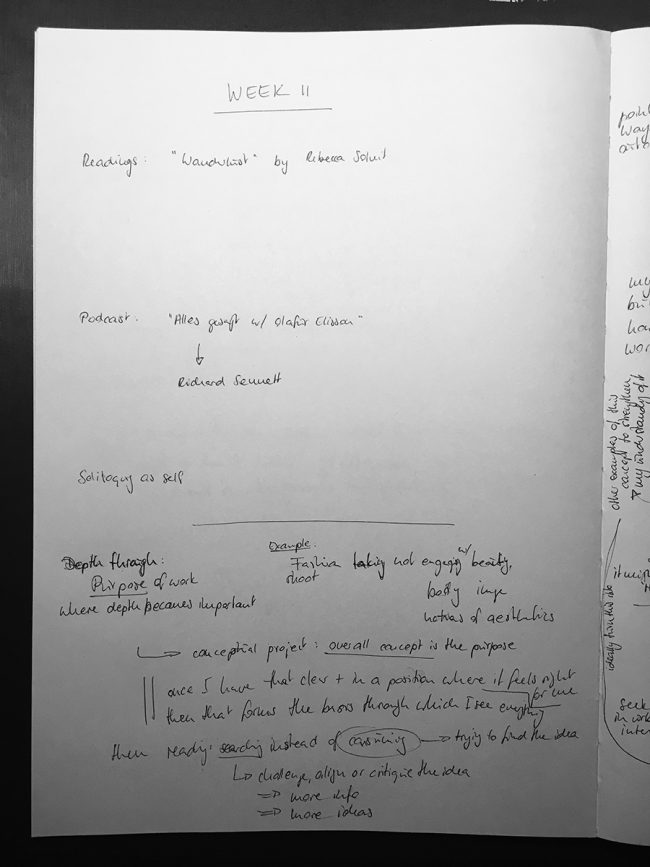

Feedback

How can my work get more depth? – Depth through purpose of work.

What's the purpose? – Probably conceptual project.

> Overall concept is the purpose.

How does the reading help? What do I exactly do?

1 Reading as consuming.

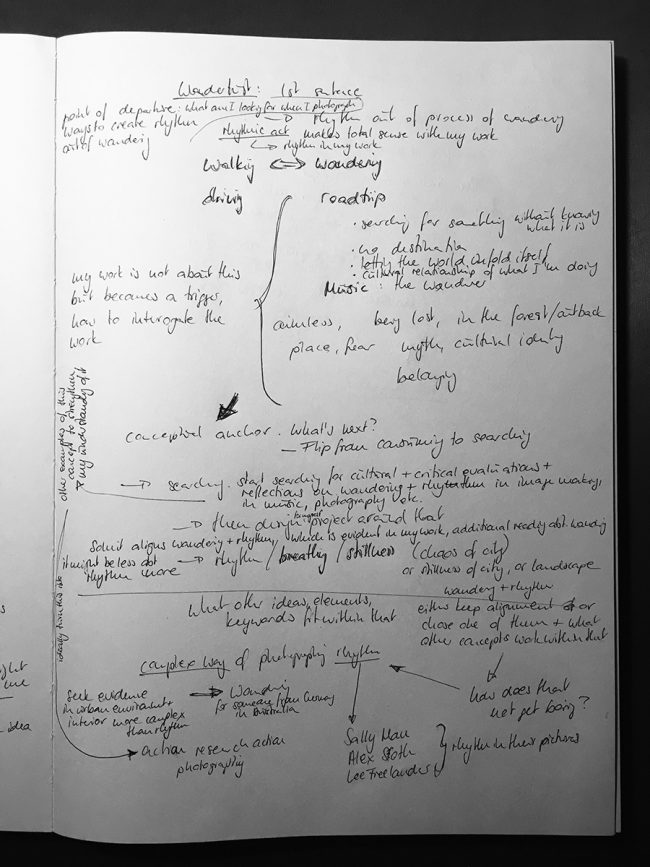

Example Wanderlust. Wandering as opposed to walking, like a road trip, with a rhythm. My work has rhythm. So, my work is not about this but this becomes a trigger, how to interrogate the work. > conceptual anchor

2 Flip from consuming to searching.

Start searching for cultural and critical evaluations and reflections on wandering and rhythm in image making, music, photography etc.

> other examples of this concept to strengthen my understanding of it

3 Design for myself a project around that.

Turning concept into photography by action – research – action. Either keep alignment or chose one of them and what other concepts, keywords, ideas, elements work within that.

How does that not get boring? – Find a complex way of photographing that concept.

In other words:

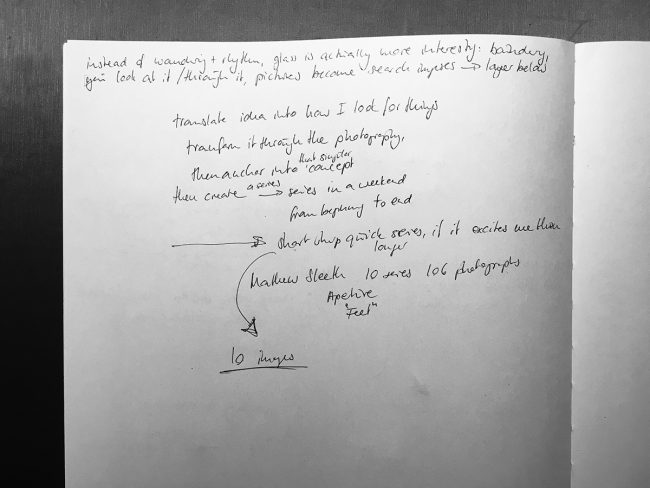

Translate idea into how I look for things.

Transfer it through the photography.

Then anchor this into that singular concept.

Then create a series.

Assignment: Make a series of 10 pictures with one underlying concept until next week.

Notes